О Гумилёве... / Драматургия

An Acmeist in the Theater: Gumilev`s tragedy the “Poisoned tunic”

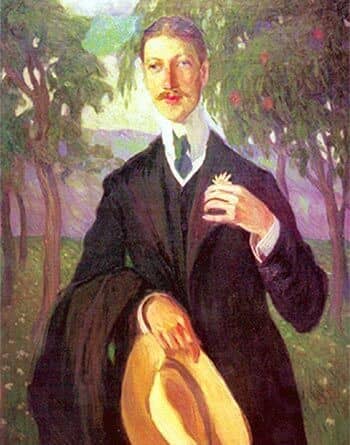

Toward the end of his life, Nikolaj Gumilev reportedly told one of his students, “I feel a real Lope de Vega awakening in myself. I will write hundreds of plays” (Odoevceva 1968: 434).

Of course, Gumilev was unaware of the brevity of the creative span left to him, and this prediction turned out to be overly optimistic. Still, it indicates that Gumilev had a deep interest in the dramatic art that is belied by the paucity of his output in the genre. Of the Acmeists, only Gumilev applied himself to drama seriously, producing seven complete plays in widely varying styles. Still, one of the “cornerstones” of Acmeism, as proclaimed in Gumilev's manifesto, was Shakespeare, “who showed us the inner world of man” (1968, 4: 175). And the motivation for Acmeism's emphasis on the Apollonian principle was Nietzsche's Birth of Tragedy. Gumilev's drama has received little attention, and there has been no examination of Acmeist dramatic theory.1 This article argues that Gumilev's and Mandelshtam's comments on drama and theater reveal a poetics of drama that is consistent with Acmeist artistic and cultural values.

Since Acmeism was proposed as a reaction to the mysticism and theurgy of symbolism, it is not surprising to find the Acmeists critical of symbolist drama. In a review of Ernst Toller's play Mass Man, Mandelshtam recalls

the recent past so painful to remember (God forbid it should be resurrected), when He, She, It, and other dramatis personae wreaked havoc among the impressionable Russian intelligentsia.

(1979:208)

By contrast, in the German author's work, Mandelshtam admires “the pathos of high tragedy”, even if ineffectively realized, as compared to the “pallid, intellectual impotence” of Russian prerevolutionary symbolist works (1979: 208).2 Gumilev voiced similar criticism of symbolist drama in an interview from 1917 published in the London journal The New Age. Referring to the theater of Maeterlinck as one of “pale events and pale movement and emotions”, he foresaw a new theater “full of passion and action and noble moments”.

Of recent dramatic essays in Russia, the attempts of such producers as Meyerhold and Evreinov to restore the old Italian comedy are bound to turn out a failure, simply because the form is too shallow and superficial, and in no way attains the depth and tragicalness so characteristic of the present time with its mighty discoveries, its War and its revolution. (Rusinko 1979: 82,83)

Acmeist criticism of symbolist drama was directed, then, at both form and substance. The Acmeist manifestos rejected the otherworldly mysticism of the symbolist movement, its subjectivity, amorality, ambiguity and abstraction. The Acmeists were bound to oppose, then, the symbolist theater of stasis and mood that dramatized man's inner experience at the expense of plot and movement, that was preoccupied with death and extolled the mask and the marionette, that disdained the mundane and strove toward the unity of opposites in a mystery of totality that approached liturgy (Segel 1979:50-78). As they did in poetry, the Acmeists demanded that drama deal with earthly reality and human psychology, that it uphold ethical and intellectual values and portray the dynamism that they felt in the phenomenal world.

Gumilev was quite specific about the purpose and responsibility of drama.

Epics always follow after the events they celebrate. But we are now in the midst of great events, and, therefore, this is a time for drama, and will be so perhaps for a long while yet... When a poet of today feels responsible for himself before the world he strives to turn his thought to drama as the highest expression of human passion, of purely human passion. (Rusinko 1979: 83)

Indeed, Gumilev's interest in drama seemed to peak in the revolutionary years. His three most substantial plays are from the 1916-1918 period, and in addition to his classes in poetry, he gave a course on dramaturgy at the literary studio of the House of Arts in post-revolutionary Petrograd. A report of “works in progress” in the journal of the House of Arts indicates that he was working on a historical play entitled The Conquest of Mexico at the time of his death ("Nenapechatannoe" 1921:74).

Gumilev also reportedly dreamed of the future production of his plays.

They will be produced here as in Spain in the seventeenth century, grandly and luxuriously, with all kinds of technical innovations and with musical accompaniment. (Odoevceva 1968:435)

While in Paris in 1917-1918, Gumilev entered into collaboration with Michail Larionov and Natalija Goncharova on ballets based on two of his plays, with the idea of having them produced by Sergej Djagilev and his Ballet Russe. In the New Age interview, he bemoans the heavy expenses of production that make theater directors unenterprising.

This is a great pity, since in a new repertoire of verse dramas there would be room both for new painters and new composers, who are at present just as remote from the public as writers are.

(Rusinko 1979: 82)

This synthetic theater art remained a dream, however.3 Larionov suggests that for Gumilev, with his Acmeist orientation to the word, the adaptation of his work for the ballet theater dominated by movement and music was difficult (Struve 1970: 409). In spite of Gumilev's continual emphasis on action, Acmeist drama is clearly a drama of the word.

One of the areas of clear disagreement between Acmeist and symbolist poetics was on the possibilities and the means of communication. It is idle ,” wrote Maeterlinck, “to think that, by means of words, any real communication can ever pass from one man to another” (Green 1986:10). So symbolist drama elaborated an incantatory idiom, produced by the extensive use of pauses, segments of silence, the almost hypnotic repetition of words and phrases, and the carefully orchestrated use of sound (Segel 1979: 53), Language attained to music, action dissolved into song, mime and dance, and drama returned to its origins in Dionysian ecstasy.

Nietzsche's influence on Russian art is just beginning to be appreciated and examined (Rosenthal 1986). In reference to drama, his Birth of Tragedy cannot be overlooked, Nietzsche recognized the ritual basis of Greek tragedy and stressed the value of myth. Asserting the primacy of music over language, he predicted that myth and tragedy would be reborn through music (55-56). The Russian symbolists argued among themselves concerning the proper interpretation of Nietzsche's views on theater, but they did not move far from his essential positions. Drama, in their view, was bom “out of the spirit of music”, out of the ecstatic sacrificial Dionysian rituals. Vjacheslav Ivanov wrote that “the drama [...] is drawn toward music, because only with music's aid is it able to express its dynamic nature, its Dionysian aspect, to the full” (1986a: 117).

Among the ancients, Ivanov and the symbolists were drawn to Aeschylus, the first of the Greek tragedians, favorite of Nietzsche, who was closest to the ecstatic and religious wellsprings of Greek drama. The antinomy of Aeschylus among the ancient Greeks, according to Nietzsche, was Euripides. It was Euripides, said Nietzsche, who caused the degeneration of Greek tragedy by diminishing the role of the chorus, by reproducing reality and everyday life on the stage, and by creating a revolution in theatrical language. His movement toward a more critical or moralistic vision of the world was regarded by Nietzsche as a diversion from tragic wisdom and a distortion of the truth, and it resulted in the attenuation of the Dionysian element of drama in favor of the epic-Apollonian (Hinden 1981: 253).

To separate this original and all-powerful Dionysian element from tragedy, and to reconstruct tragedy purely on the basis of an un-Dionysian art, morality, and world-view — this is the tendency of Euripides. (Nietzsche 1968:81)

It was Nietzsche's opinion that Euripides' attempt to ground the drama in the Apollonian principle meant the demise of Greek drama, but this un-Dionysian tendency of Greek drama became the model for Acmeism. The influence of Euripides came to the Acmeists through the intermediary of another classicist among the Russian symbolists, Innokentij Annenskij.

Annenskij, one of the mentors of the Acmeists, was best known as a classical philologist whose most important achievement was the translation of all of Euripides' surviving plays. In distinction from Ivanov and Nietzsche, Annenskij admired Euripides for his attention to detail, his willingness to alter old myths to suit his purpose, and the playfulness of his language. Annenskij's long creative involvement with Euripides is apparent in his own dramatic work. Discussing his dramatic method, Annenskij rejects the “easy” way of “archaeological stylization” for what he called the “mythic” method, which

enabled the author to enter more deeply into psychological and ethical questions and to fuse more effectively the world of antiquity with the modem soul. (Annenskij 1968:248)

Gumilev strove for this same effect in The Poisoned Tunic (Otravlennaja tunika).

In 1913, the year of the appearance of Acmeism, Annenskij published his last tragedy Thamyris Kitharodos (Famzra Kifared). It retells the legend of Thamyris, whose pride in his musical ability prompted him to challenge the muses. Annensky modifies the myth by altering the motivation for the artist's challenge. It is not pride that moves him, but a desire to know and attain the ideal. Also in distinction from the myth, Annenskij's Thamyris does not actually compete with the muse. Instead, her songs, not meant for mortals, captivate him, and he becomes aware of the futility and impropriety of his aspirations to the ideal, that is, of the distance between gods and men. After the failure of his aspirations and the loss of his musical gift, Thamyris becomes indifferent to the world and seeks oblivion. Vyacheslav Ivanov saw Annenskij's pessimism as the result of his general scepticism, his reluctance to bridge the gap between the human and the divine by taking man into the realm of the gods.

An individual's assertion of his divine I [in Annenskij] ruptures his links with the earth and calls down inevitable retribution on his head; but there on the divine plane... Beyond this point, however, our poet does not venture; here he finds himself too lacking in the strength of religion — or is it only a 'chaste reserve' — to make any kind of assertion. (Ivanov 1986: 124)

It was precisely the “chaste reserve” of Annenskij that appealed to the Acmeists. (Recall Gumilev's use of the term 'chastity' in his manifesto to refer to Acmeism's approach to the unknown.) The influence of this work of Annenskij's is obvious in Gumilev's play Akteon (1913), in which the hero is punished for his aspirations to divinity (Baslcer 1985).

Thamyris Kitharodos was reviewed by both Mandelshtam and Gumilev. It was the only drama to be included by Gumilev in his 'Letters on Russian Poetry' for the journal Apollon. In his review, Gumilev commented on Annenskij's vivid graphic language and psychological nuances, and his combination of the ancient with the contemporary (1968,4: 330). He also noted the dual musical motif — the story of Thamyris and the background against which it is played out, that is, the Apollonian world of art against the Dionysian background of crazed maenades and jovial satyrs. The connection he feels between this work of Annenskij's and the newly proclaimed Acmeism is revealed in his characterization of Annenskij's style as “beautiful difficulty”, which recalls Acmeism's aspiration always to take the path of greatest resistance (1968,4:173).

Mandelshtam saw Thamyris as primarily “a work of verbal creation”. “Annenskij's faith in the power of the word”, he says, “is boundless”, and in his commentary, Mandelshtam expresses a reversal of the Ivanov-Nietzschean exaltation of music over language.

While reading Annenskij's stage directions for the dances and choruses, you perceive them as though they were being realized before your eyes; thus the staging of this work can add nothing to the splendor of the text of Themyris the Cithara Player itself. Why, indeed, should the timpani and flutes, once they have been transfonned into words, be returned to the primitive condition of sound? (101-102)

Annenskij's faith in the power of the word was also Acmeism's, In his article on the Moscow Art Theater, Mandelshtam decried the turn of the century intelligentsia's “distrust of the word”.

The path to theater went through literature, but they did not believe in literature as a reality: they did not touch or hear the words... Instead of reading the word, people searched for whatever might shine through it.,. The highest form of expressiveness is found in the structure of speech, verse, or prose... In the theater one must speak in order to move because theater is entirely contained in the word. (189-190)

The poetic word was the basis of Acmeist poetics, and Gumilev's Acmeist drama is emphatically a poetic drama. In the New Age interview, Gumilev foretold a renaissant poetic drama to take the place of the prose theater.

Moderm poets have the advantage of being much more emancipated than their forerunners, and poetry itself has become richer in nuances and energetic expressions. When a rather vulgar play by Rostand can be so successful in Paris,4 certainly plays written by better poets might attain enormous success. But the public must be educated to them, if only by repetition. The public does not like innovations, but it is easily persuaded to admire whatever is often placed before it,.. The new theatre, I imagine, would not be one of pale events and pale movement and emotions, like that of Maeterlinck, but, on the contrary, would be full of passion and action and noble moments. (Rusinko 1979: 82-83)

At the very time that Gumilev voiced these thoughts on drama, he was engaged in writing his most extensive dramatic work, The Poisoned Tunic, A Tragedy in Five Acts (1968, III: 137-210). This play reflects the influences mentioned above and illustrates the dramatic values of the Acmeists — an emphasis on the word and on the inner life of man in a depiction of human passion and great events that manifests the poet's “responsibility for himself before the world”.

Written during Gumilev's stay in Paris and London in 1917-1918, The Poisoned Tunic remained unpublished after the poet's return to Russia. The text was discovered by Gleb Struve among the materials that Gumilev entrusted to his London friend Boris Anrep, and it was published for the first time with Struve's extensive notes and commentary in 1952. The action takes place in the court of Justinian and Theodora in seventh century Constantinople. The empress Theodora is the evil genius at the center of the plot who manipulates the other characters, including her corrupt, if more sympathetic, husband. She is motivated by the fear of having her immoral past exposed to the emperor and by her jealousy of Justinian's daughter Zoe, the bright light of purity and innocence in the depraved Byzantine world. Thirteen year old Zoe is betrothed to the tsar of Trebizond, an upstanding moral man and brave warrior, but a prosaic and uninspired lover. Unknown to Zoe, her father plans to murder the tsar for political reasons immediately after the wedding by means of a poisoned tunic. Into this tense situation comes Imru' al-Qays, a Bedouin poet and warrior, who has taken a vow of abstinence from the pleasures of the senses until he can avenge his father's death. Aided by Theodora, and by dint of his poetic eloquence, Imru seduces Zoe, whose “triumphant, innocent beauty” causes him to break his vow, only to abandon her when Justinian offers him an army to reconquer his father's kingdom. In the rapid denouement, the tsar of Trebizond commits suicide by throwing himself from the scaffolding surrounding the still unfinished Hagia Sophia, and Justinian takes retribution against Imru and Zoe by sending the poet the poisoned tunic as a “sign of good will” and by dispatching his daughter to a convent. As the play ends, Theodora looses a volley of invectives against the now emotionally prostrate Zoe.

The only additional character in the play is a eunuch who plays the functional role of messenger and provides exposition. Contributing to the concentration of the plot is the play's neo-classical form and structure. Gumilev carefully observes the unities of time, place and action.5 Among the papers given to Struve by Anrep are Gumilev's notes and rough drafts of the play, which indicate that the acts were carefully planned to focus each on an individual character, bringing him into contact systematically with all of the other forces in the play (1968, III: 266-272). The notes also contain enigmatic tags to classify each character. They are summarized here, as they appear in the notes.

Imru (Subjectifs) Titan

Zoe (Passifs)

Tsar (Objectifs) Olympian

Theodora (Intellectuels)

Justinian (Actifs)

Eunuch (Corporel)

Of the main characters, only Zoe and the tsar of Trebizond are invented, but Gumilev follows legend and popular culture rather than history in presenting Theodora as the embodiment of evil and her relationship with Justinian as discordant.6 The character of Imru is faithful to the accounts of the life of the pre-Islamic poet Imru' al-Qays, and the story of the poisoned tunic comes from legends about him (Nicholson 1962: 104). In The Poisoned Tunic he captivates Zoe with a poetic account of his romantic exploits, which Gumilev adapted from Imru' al-Qays' Mallaqat.

All of Gumilev's dramatic heroes are poets (Driver 1969: 338), and in The Poisoned Tunic Imru's speeches intensify the sense of poetry that pervades the play. The language of the play is lofty and elevated in style, and in the blank verse of Elizabethan tragedy. Only Imru, the poet, speaks in rhyme, though not consistently but predominantly in highly emotional passages and always when he speaks about love. Gumilev's notes also contain descriptions of the speech style of each character. For example, Imru's language is described as follows: “Quick words, sharp style, full of antitheses and rhetorical movements, exclamations, etc. [...] tragic.” The tsar of Trebizond's style is “oratorical, explanatory, enlarging the small”, and Justinian's is “refined and narrative” (1968, III: 269). Language, then, is one of the chief means of characterization. Mandelshtam carried this appreciation of language into the sphere of performance in his admiration for the actress Komissarzhevskaja's pure and clear expression:

Amid the grunting and roaring, the whining and declamation, her voice [...] grew stronger and more mature. The theater has lived and will live by the human voice. (1986:112)

As a drama of the word, the tragedy depends on its language. Gumilev undoubtedly would agree with Mandelshtam's theatrical assessment that “the director is hidden in the word” (1979: 189). Stage directions are few and laconic. Appearances and emotional states are communicated through dialogue and imagery (“And now you're trembling like a captured bird” (2.2); “I feel like a bowstring / Pulled taut by some mighty arm” (3.3).7 The significant action of the play, the seduction and suicide, takes place offstage, and the tunic of the title is never in evidence. Rather than the theatrical images that predominated in the theater of the symbolists and avantgarde (Driver 1970: 125), Gumilev depends on verbal images to focus the issues, to reveal character, and to create atmosphere and moral tone.

Like Shakespeare, Gumilev uses thematically relevant clusters of images to focus the reader's attention and direct his sympathy. The imagery of the play is very close to that of the love poetry of To the Blue Star (K sinej zvezde), written contemporaneously with The Poisoned Tunic (Rusinko 1977). Images of stars and flame fill Imru's speeches, and while on one level Gumilev is very sympathetic to this largely autobiographical warrior-poet, the development of imagery presents an unflattering picture of Imru's inner moral life. In his first encounter with Zoe, for example, Imru enflames her imagination with images of “stars filled with fire, like diamonds on a woman's dress” (1.2). Zoe describes Imru as having eyes like shining stars (2.2), and during their night of love, she says, “The stars sang so sweetly in the sleepy sky” (4.4). The contrasting character of the tsar of Trebizond is clear when he returns from his exploits, having found only “clear, unfeeling stars” (2.2). But it is Theodora, ruled by the intellect, according to Gumilev's classification, who penetrates the rhetoric and notes that Imru's soul is “blacker than a starless night” (3,3). Imagery of fire and lightning describes Imru's passion. Zoe entered his life “like a fire” (2.2), and he cannot forget her, “Just like a small, red flame / Flicks out, disappears, but the skin is burned” (3.3). His passion bums like a forest fire (3.3), ignited by “flying lightning” (3.5; 4.1). However, the fire of passion is also destructive. “Your words scorch me” (3.5), protests Zoe. After the seduction “a strange lightning” (4.1) torments Imru in a dream, and Justinian describes the death Imru will suffer from the poisoned tunic: “A dry fire will bum him to ashes” (5.4).

Another cluster of images points to Imru's wild, animal-like nature. In his exposition the poet presents himself as a “wounded bird” (1.1), but as the action develops he is described by the other characters as “a beast without the shadow of a human soul” (4.4), “a tiger scenting his prey” (3.4), and in Justinian's vision, he dies howling like an animal (5.5). The tsar of Trebizond, on discovering Imru's duplicity, tells him, “You were a tiger, I thought — now I see you are a hyena / Covered with a tiger's striped hide” (2.4), Significantly, Imru later uses the hyena image to apply to Theodora (3.3). A connection between Imru and Theodora on the level of imagery is observed also in their independent use of the loaded metaphor “serpent” to describe the poet. In boasting of his previous amorous adventures to Zoe in their first encounter, Imru describes how he crept into the guarded camp “like a serpent” (1.2). This occurs in the passage adapted from the Mallaqat poem of Imru' al-Qays, but significantly, in the original the metaphor is absent, indicating that the serpent metaphor was Gumilev's deliberate artistic choice. Theodora repeats the image in her feigned avowal of love for Imru (4.3).

By contrast, the tsar of Trebizond is characterized by religious imagery. For him Zoe's eyes are not the “gazelle eyes” of Imru's poetic speech (1.2), but “sinless, like paradise” (2.4), and she is “more sacred than the Holy Gifts” (3.4), “a world containing a throng of six-winged seraphim and the Three-in-One Creator” (variant, III: 277). The tsar's Christianity is made explicit when Theodora, whose hypocritical use of religious references is ironic, reminds him not to avenge an insult: “Remember, Tsar, that you are a Christian” (2.4). From the tsar's initial appearance when he exclaims “Glory to Mary!” (1. 4) to his appeal to Christ at his death (5.4), he is clearly out of place in morally depraved Byzantium.

The tsar is also most closely associated with the angel imagery that pervades the play. When told by Zoe that she had spoken with someone who seemed to be a vision (meaning Imru), the tsar responds, “So it was an angel. / You are a saint, Zoe, and of course / Heavenly spirits come to you” (2.2). Theodora plays on this identification with her sarcastic taunts to the tsar about Imru: “He can come to her at night in her dreams / Shining like a golden angel” (2.3). The angel imagery that refers to Imru is ironic, however.8 In a more reverent manner, the tsar becomes identified with Zoe's guardian angel, as he vows to stand guard with his sword at her door (3.4), and in Zoe's vision of her guardian angel crying at her seduction (4.4; 5.1). If he had considered Zoe saintly and angelic earlier, now he has come to a new realization:

I remember an old proverb,

I don't know where I heard it.

That a woman is not simply human

But a gentle angel and a ferocious demon

Mysteriously joined together.

With the man she loves she is all angel,

And all demon to the man she does not love.

(4.4)

In the end, it is the tsar who stands “at a terrible height / With his face to the south, gilded by the sun / Like a spirit” (5.4). But unlike the winged angels he so often invoked, he falls to the earth like any man.

If there seems to be something god-like in the tsar of Trebizond, this would be consistent with Gumilev's classification of him as “Olympian”, to contrast with Imru's label, “Titan”. The terms derive from The Birth of Tragedy, where Nietzsche presents his image of Greek tragedy as the unity of the Apollonian and Dionysian motives, which were born of and are akin to the forces represented by the restrained Olympians and the chaos-producing Titans:

Out of the original Titanic divine order of terror, the Olympian divine order of joy gradually evolved through the Apollinian impulse toward beauty... This apotheosis of individuation [Apollonianism] knows but one law — the individual, i.e., the delimiting of the boundaries of the individual, measure in the Hellenic sense. Apollo, as ethical deity, exacts measure of his disciples, and, to be able to maintain it, he requires self knowledge. And so, side by side with the aesthetic necessity for beauty, there occur the demands “know thyself' and "nothing in excess”; consequently overweening pride and excess are regarded as the truly hostile demons of the non-Apollinian sphere, hence as characteristics of the pre-Apollinian age — that of the Titans' and of the extra-Apollinian world — that of the barbarians.

(Nietzsche 1968:42,46; original italics)

Imru's nature is clearly Titanic. He is impulsive and extremist, knowing no measure or limit, filled with an ungrounded sense of pride. He boasts equally of his virtues and his sins, and he is incapable of checking his passions. Imru himself recognizes this fault as he explains his illicit attraction to Zoe as a result of his inability to cope with passion (insertion in 2.4, HI: 279). Justinian, the builder and sustainer of a stable, hierarchical world order represented by the cathedral Hagia Sophia, fears the Arab, who has the “blood of a savage” and “loves his freedom” (2.1). Referred to throughout as a “beast” and a “savage”, Imru's last words, as he abandons Zoe and the civilization of Constantinople to lead the troops granted him by Justinian, are: “There are my barbarians!” (“Vot goty!”, 5.1),

The tsar is by contrast restrained, balanced, ruled by the ethical principle and completely in possession of himself. Though he lacks Imru's creativity, he reflects the Olympian awareness of “an exuberant, triumphant life in which all things, whether good or evil, are deified” (Nietzsche 1968:41). He speaks lovingly of “the seas and broad deserts”, his

small, incomparable city

with its wonderful crisscrossed net of narrow streets

Running from shore to shore,

And its one great square where often

I sit and hand out justice

Beneath the shade of a hundred-year-old tree.

(1.4)

The image of the tsar weighing the scales of justice emphasizes his ruling trait, balance. He loves the ring of steel in battle, but offers to give up the command to Imru: “I am happy today; I want others to be happy, too” (2.1). Characterized by what Nietzsche calls superficial “Greek cheerfulness”, the tsar continually calls attention to Imru's gloominess. And yet he is aware of another way of being. He tells Zoe:

I've never seen a land

Where, like a clear-singing bird, like a rose bush

Unknown happiness comes flashing by.

I've watched for it at every crossroads,

Behind every cloud that ran out onto the sky,

And all I've seen is bald, insolent mountains

And clear, unfeeling stars.

But I know, oh, how I know it —

There are suchplaces on the earth

Where man does not walk, but dances,

And sweet love does not know pain.

(2.2)

Nietzsche writes:

The effects wrought by the Dionysian also seemed 'titanic1 and 'barbaric' to the Apollinian Greek; while at the same time he could not conceal from himself that he, too, was inwardly related to these overthrown Titans and heroes. Indeed, he had to recognize even more than this: despite all its beauty and moderation, his entire existence rested on a hidden substratum of suffering and of knowledge, revealed to him by the Dionysian. And behold: Apollo could not live without Dionysus! The 'titanic' and the 'barbaric' were in the last analysis as necessary as the Apollinian. (Nietzsche 1968:46)

In this sense, as well as in other obvious psychological aspects, Imru and the tsar are complementary interdependent characters. Instead of emphasizing the blending of the Apollonian and Dionysian, Gumilev stresses the unreconcilable warfare of the Titans and the Olympians. In this respect Gumilev follows Annenskij and Euripides, rather than Nietzsche and Vyacheslav Ivanov's symbolism. Nietzsche had argued that

in Euripides there occurs a rationalization of the Dionysian/ Apollonian synthesis, which as a union of complementary principles can be grasped only intuitively by means of the imagination... Euripides bifurcates the Dionysian/Apollonian unity and sets psychological forces in dialectical opposition to each other, whereas Nietzsche maintains that tragic complexity stems from a union of these complementary forces.

(Hinden 1981:254,256-257)

Thus, the tsar and Imru, as disconnected parts of a whole, are both doomed to destruction, but while Imru dies a humiliating, low death, the tsar s death is heroic and an act of Christian sacrifice.9

As reported by the eunuch, the motivation for the tsar's method of suicide was the Scythian tradition that a man be buried beneath the foundations of a temple to insure its stability. With the eunuch he climbed the “monstrous scaffolding / Like the ribs of Leviathan or Behemoth”. Having figuratively confronted the monster, that is, the whole order of Byzantine society, as represented by the cathedral, he began to speak.

He said that this city

And its buildings, its palaces and its roadways

Like all words, desires and meditations,

That rule over man

Are the legacy of the dead to the living,

That there are two worlds, unequal:

In one of them, huge, live geniuses and heroes,

Who fill the entire universe with glory.

And in the little world — we, their pitiful descendants

Slaves of necessity and fate.

Then he said that death was not terrible,

That Heracles and Julius Caesar had died,

Mary had died, and Christ had died,

And suddenly, as he said Christ's name,

He stepped forward, over the edge of the wall, where the air

Was penetrated with the noonday blaze...

And he seemed to be standing

Over an abyss, having conquered earth's gravity;

In frightful confusion, I closed my eyes

For just one second, for half a second,

When I opened them, before me —

O woe! — I saw no one.

(5.4)

A moment later what remains of the tsar is “a pile of meat and bones that had no human shape”.

The tsar, like Annenskij and the Acmeists, does not attempt to bridge the gap between man and the gods. He recognizes the limits of the world and accepts the restraints of gravity and the human condition, including death. But Gumilev's message is that it is only in accepting these limits that man can transcend them and, even momentarily, conquer earth's gravity, which was such a powerful symbol of reality for the Acmeists. The tsar dies as Christ did, for the sins of others, and there is a hint that his death has a productive impact on the politically corrupt and morally depraved world he leaves behind. The eunuch reports that the stone masons who discovered the body, hard and simple people who loved the tsar for his courage and his lofty spirit, were heard muttering curses in the direction of the imperial palace. “They suspect mystery everywhere” (5.4). This may be another of Gumilev's poetic hints at the connection between Acmeism and the ideals of Freemasonry (see Basker 1985: 512-517).

The political implications of the play are never far from the surface. Gumilev had told his London interviewer that “in the midst of great events”, when the “poet feels responsible for himself before the world”, he turns to drama to express that responsibility. Comfortably fixed in London and Paris at the time when his own country was experiencing the throes of revolution, the poet/dramatist undoubtedly knew the nostalgia expressed by the tsar of Trebizond for his homeland. Even more might Gumilev sympathize with Imru's conflict between his infatuation with Zoe and his vow to reconquer his father's kingdom, since Gumilev was similarly torn between his Parisian love for “the blue star” (who was, like Zoe, engaged to another man), and the pull to return to Russia. In an earlier draft of the play there are two specific comments on the concept of the homeland (rodina) that were excised in the fair copy. As he seduces Zoe, breaking his vow to reconquer his father's kingdom, he asks rhetorically, “What is the homeland to a man? The threshold / Of the door leading to astral villages” (III: 284). In the rough draft of the final act, Imru tells Justinian, “I cherish two homelands for my heart, / One in Arabia, the other — here” (HI: 290). This ambivalence is absent from the final edition, perhaps for the personal relevance it might reveal. In any case, a serious theme of the play involves power and politics, and the dramatic focus shifts to the character of Zoe.

Gumilev's notes indicate an explicit political significance attached to Zoe. In the plan for the fifth act, which focuses on her, Gumilev seems to identify her with Byzantium — “Portrait of Zoe-Byzantium”, and in a crossed-out comment he notes, “Caesar speaks of the political role of Zoe” (III: 272). Though the action of the final version does not exactly follow the preliminary plan, Zoe's role is clearly symbolic. As the daughter of the emperor, she is the political prize fought for by the rival lovers, envied and schemed against by the depraved empress, and exploited for political gain by her father. “What are a girl's tears / Compared to the needs of the empire?”, declares Justinian at the eunuch's objection to his poisoning of the bridal tunic. When Zoe at last learns of Justinian's plan and questions her father, his answer reveals his political philosophy.

Why does lightning flash in the sky,

Burning the property of the settlers,

Why are there storms and desert winds.

Why are there poisonous flowers?

My child, the laws of the state,

The laws of human destiny

Here in the world, which die Lord leads

Along inscrutable pathways.

Are the same as those that rule

All creatures, the grass, and the grain of sand.

(5.3)

Rather than condoning political brutality, this philosophy expresses a faith in a lawful cosmos that works to the good, despite the appearance of evil. It recalls the religious and ethical approach to politics that characterized the early Middle Ages, that period so beloved of the Acmeists. As developed most vividly in the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas and the work of Dante, medieval civilization was founded on the sanctity of law, which was believed to be an emanation of the reason of God, whereby everything in heaven and earth is ruled. Human society and its institutions were seen as “a typical level of the cosmic order, in which the same principles obtain that manifest themselves in different forms on the other levels” (Sabine 1961:252).

The controlling social conception is that of an organic community in which the various classes are functioning parts, and of which the law forms the organizing principle. The rightfully controlling force is the well-being of the community itself, which includes the eternal salvation of its members. In this vast system of cosmic morals all men, and indeed all beings, are included. From God at the summit down to the meanest of His creatures all act their part in the divine drama that leads to eternal life.

(Sabine 1961:261)

This world-view recalls the philosophy expressed in the Acmeist manifesto that asserted the value of the most insignificant phenomena in an orderly universe, with all things fitting into a harmonious hierarchy crowned by God. In the Byzantine society of the play, Justinian plays the active role of builder, to establish and maintain this ideal, ordered universe. Symbolically he constructs a temple at God's command.

By the great mystery of anointing

You commanded me to this royal labor, desiring

That the world become a temple, and above it,

Poised like a cupola — imperial power

Crowned with Your cross, O Lord.

(1.5)

On a literal historical level, Gumilev's Justinian is honored for his great legislative work (also in the poem 'Bolon'ja', I: 253), the compilation of Roman law, even while he actively circumvents the moral law toward the 'higher' purpose of sustaining an 'orderly' universe. Dante placed Justinian in Paradise among the spirits of those who sought honor in the active life (Canto X), and Gumilev's notes accordingly classify him as “actifs”.

Given this context, the question of social hierarchy becomes significant, and in The Poisoned Tunic it takes on ethical import. Justinian berates Zoe not on moral grounds, but because she has forgotten her proper station. “You, heir to the throne of Byzantium, / You gave yourself to a wandering Arab?” (4.4). That Imru is also conscious of the force of rank and position is clear from his initial retort to Theodora, “Is a Bedouin to dream / Of the emperor's daughter?” (1.3). While on one level his sin is the violation of his personal vow, on the social or cosmic level, it is the breach of natural order.

Zoe's objections to her father's plans point up the problem of the individual in the political or cosmic order. She acknowledges that for Justinian, as “Caesar, the Lord's anointed”, good and evil are intertwined, leading to glory in heaven. “But I, I'm just a girl,” she says, “Let me be good, let me be happy!” (5.3). Having first advised “blue-eyed submission”, which, he says, was created by God to allow harmony in the world, Justinian subsequently gives in to Zoe's plea for the sake of her dead mother. However, in the next scene it becomes clear that Zoe's interference has resulted in no gain; the tsar has committed suicide, and when Justinian learns of Zoe's love for Imru, he retaliates by presenting the poisoned tunic to the Arab poet, a conclusion that is more painful for Zoe than the original scheme. There is no room, then, for simple individual happiness in the chaotic Byzantine world of intrigue, or more generally, individual happiness is of minor importance in the divine plan of the universe, and Zoe unwittingly becomes responsible for the death of both the tsar and Imru.

Zoe's crime would seem to be minor — the result of her youth, her innocence and her credulity. The destruction that ensues, as always in tragedy, is vastly disproportionate to the cause, and Zoe is a true tragic heroine, whose punishment far outweighs her sin. The play might have ended with the revelation of Zoe's guilt, but Gumilev goes a step further, adding a final scene, totally unmotivated by the previous action, in which Zoe is subjected to a verbal scourge by Theodora. The empress, whom the spectator/reader has seen as evil incarnate throughout the play, now assumes the high moral ground and Zoe, with whom he has commiserated and sympathized, is berated as the villain. And to the reader's dismay, the conclusion tends to validate Theodora's previous self-justification: “All women are the same” (3.1). In the final speech of the play, Theodora notes that Zoe has ancient Roman blood, while her own is plebeian, that just yesterday Zoe was a virgin, while Theodora knows all the whorehouses and low taverns in Constantinople.

But I'm more pure than you, and before you

I stand with horror and disgust.

All the palace filth, all the sins of your ancestors,

The treachery and baseness of Byzantium

Lives now in your unknowing, childish body.

As death lives sometimes in a flower,

Growing out of a plague cemetery.

You think you are a woman,

But you are a poisoned bridal tunic,

And every step you take is death.

Everywhere you look you bring death,

And the touch of your hand is death!

The tsar of Trebizond is dead,

Imru will soon be dead

But you are alive, fragrant with gloom.

Pray! But your prayers frighten me.

They seem like blasphemy.

Theodora exits and Zoe falls on her knees, her face to the ground, as the curtain falls.

At the conclusion of the play, then, we find that the central symbol, the poisoned tunic, is also a metaphor for the tragic heroine, and the poison is in the ancient Byzantine blood-line into which she was bom. If she is guilty, it is not apersonal culpability but a hereditary guilt she bears, which accounts for the pathos of her position, for the simultaneous guilt and guiltlessness which is the essence of her tragedy. The sense of tragic determinism in her fate contributes to the passivity that Gumilev saw as her identifying characteristic.

The theme of inheritance runs through the play. In addition to Imru's vow of revenge, there is reference to the tsar of Trebizond's s patrimony; he preserves his father's armor and his mother's worn out clothes, as well as the cross used by the apostle Paul to Christianize his people. By contrast, Theodora's suspect parentage is part of her degeneracy. In the tsar's closing speech, he universalizes the concept by his comment on the legacy of the dead to the living (5.4, see above). And by concluding his play with the revelation of Zoe's inherited iniquity, Gumilev highlights the issue.

The question of inherited power and responsibility forms part of the political philosophy of the plot and is related to the topical political significance of the play. On his return to revolutionary Russia, Gumilev was an open and proud monarchist. One of the most specific observations of his political views in this regard comes from Johannes von Gunther, a colleague on Apollon.

[Gumilev] was a [...] committed monarchist I often argued with him about it. I could accept, perhaps, an enlightened absolutism, but not at all a hereditary monarchy. But Gumilev defended it, though even today I could not say whether he really was a supporter of the Romanov dynasty. He was more likely a supporter of the dynasty of Rurik. (134)

In fact, most accounts confirm Gumilev's monarchist sympathies, though it has been suggested also that the poet had become disillusioned with the rule of the last Romanov, due in particular to the Rasputin affair (Semen Lipkin, public lecture, June 3, 1989). To be sure, the state of Justinian's Byzantium bore a certain similarity to the atmosphere of the Russian court of the last Romanov, with its growing social and political tensions, widespread corruption in government, rumors of moral depravity, a weak emperor and a dominating empress, under the mystical influence of the inscrutable peasant-monk whose motto was “Redemption through sin”, and an heir to the throne suffering from a hereditary illness.

The relationship between Russia and Byzantium, of course, is more than superficial. Since heredity is such a significant issue of the play, it is worth remembering Byzantium's cultural and religious legacy to Russia. When Constantinople fell to the Turks, Moscow declared itself “The Third Rome”, the last bastion of Orthodoxy. The reigning grand prince of Moscow, Ivan HI, was declared to be the successor of the Byzantine emperors and Caesars of Rome. To legitimate his claim, in 1472 he took as his second wife Zoe Paleologus, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor. Raised in Rome, cultured and ambitious, Zoe brought to Russia the magnificent ivory throne used in the coronation of all subsequent Russian tsars and the tradition of elaborate ceremonies, as well as the emblem of Byzantium, the double-headed eagle, which Ivan adopted as the imperial insignia. To return to Gumilev's artistic recapitulation of Byzantine history in The Poisoned Tunic, it must be noted that the historical Justinian was childless; the daughter of the play was Gumilev's invention. Gumilev's deliberate artistic choice of the name Zoe, then, seems symbolically motivated and thematically significant. The other invented character, the tsar of Trebizond, is not even given a personal name.

If there is a political parallel between The Poisoned Tunic and the situation in Russia at the time of the revolution, it implies a pessimistic outlook. The events of the plot unravel in an inevitable course toward disaster on both personal and historical levels. Victory is won by the pragmatic, expedient, immoral forces, yet the suffering of the seemingly innocent is also strangely justified as psychologically and symbolically necessary. The result is the waste of human fineness and the destruction of idealism. If there is an escape from the political corruption and moral depravity that rules the world, it is only through faith in an eternal plan of divine wisdom and spiritual transcendence that sustains the political order, despite appearances to the contrary. The pessimism expressed in the play is similar to that of a short lyric written by Gumilev probably on his return to Russia in 1918.

Omen

We left Southampton,

And the sea was light blue.

But when we put in at Havres,

It turned black.

Ibelieve in omens,

As in morning dreams.

Lord have mercy on our souls:

A great misfortune threatens.

(II: 145)

However, The Poisoned Tunic also manifests Gumilev's faith in the power of art to transform the raw material of life into an aesthetic creation characterized by clarity and harmony, and in this sense it can be seen as a triumph of artistic optimism. Observing the rules of 'beautiful difficulty', inspired by Shakespeare's dramatic method and Annenskij's adaptation of Nietzschean concepts, Gumilev created a tragedy that fully illustrates the precepts and ideology of Acmeism while it manifests the author's 'responsibility' before the world.

Notes

1. Six of his plays are contained in volume 3 of Gumilev 1968. A newly discovered two-act play Rhinoceros Hunt (Ochota na nosoroga), written apparently in 1919-1920, was published in 1987. In addition, five fragments from dramatic works are included in Gumilev 1986. The most important studies devoted to Gumilev's drama are Basker 1985, Driver 1969, Rriger 1950, and Sedkarev 1966.

2. Ernst Toller (1893-1939) is known for his expressionist plays on the theme of war. For Mandelshtam's views on theater, see also Harris 1985.

3. Only one of Gumilev's plays, Gondla, was produced professionally, in Rostov in 1920. In 1918-1919 Gumilev was active in a chamber theater established at the editorial offices of the journal Apollon. The troupe of actors consisted of former students of Mejerchol'd. Gumilev was in charge of the repertoire with projected performances of Euripides' Cyclops in Annenskij's translation, a twelfth-century mystery play, and Corneille's The Cid, translated by Gumilev. See Gumilev 1986: 85.

4. The “vulgar play” by Rostand probably refe rs to Cyrano de Bergerac (1897), the highly romantic “heroic comedy” which enjoyed tremendous popularity.

5. Gumilev's London notebook includes a list of books “to buy in Paris”. Leading the list is Aristotle's Poetics (Gumilev 1968, IV: 541). In the notes for his projected book A Theory of Integral Poetics, there is a section devoted to tragedy.

The composition of tragedy: modified rule of six. Plot, climax, denouement. Three unities. Three types: classical, romantic, mystery. In distinction from the epic — development of character.

(1968, IV: 559)

6. In addition to the Secret History of Procopius, Gumilev was most likely familiar with Victorien Sardou's play Theodora, which opened in 1884 with Sarah Bernhardt in the title role and enjoyed a long run and several revivals. For more information on sources, see Struve's commentary in Gumilev 1968,111:250-285.

7. References to The Poisoned Tunic in the text are by act and scene. The translation is based on that of Burton Raffel and Alla Burago (Gumilev 1972), though I have made substantial changes.

8. Gumilev removed from an earlier draft Imru's proposition of a night of pleasure that would transform him and Zoe into “burning angels” (Gumilev 1968, III: 274).

9. In a forthcoming article in the proceedings of the second 'Nietzsche in Russia' symposium, I argue that Acmeism's concept of Orthodox Christianity is the fulfilment of Nietzsche's Apollonianism, in contrast to Vjacheslav Ivanov's attempt to reconcile Christianity with Dionysianism.

References

Annenskij, Innokentij

1986 'Thamyris Kitharodos'. The Russian Symbolist Theatre, 247-307. See Green 1986.

Basker, Michael

1985 'Gumilyov's “Akteon”: A Forgotten Manifesto of Acmeism'. Slavonic and East European Review, 63, 498-517.

Dante

1981 The Divine Comedy (transl. C.H. Sisson). Chicago.

Driver, Sam

1969 'Nikolaj Gumilev's Early Dramatic Works'. Slavic and East European Journal, 13, 326-347.

Driver, Tom

1970 Romantic Quest and Modem Query. New York.

Green, Michael (ed. and transl.)

1986 The Russian Symbolist Theatre. Ann Arbor.

Gumilev, N. S.

1952 Otravlermaja tunika i drugie neizdannye proizvedenija (ed. G. P. Struve). New York.

1968 Sobranie sohinenij, 4 Yols. (ed. G.P. Struve and B.A. Filippov). Washington.

1972 Selected Works (transl. Burton Raffel and Alla Burago). Albany.

1986 Neizdannoe i nesobrannoe (ed. Michael Basker and Sheelagh Duffin Graham). Pari s.

1987 'Novonajdennaja p'esa N.S. Gumileva “Okhota na nosoroga'”. (ed. M.D. El'zon) Russkaja llteratura, 2, 159-163.

Gunther, Johannes von

1989 'Pod vostochnym vetrom'. Nikolaj Gumilev v vospominanijach sovremennikov (ed. Vadim Crejd). New York, 131-141.

Harris, Jane Gary

1985 'Mandelshtam's Aesthetic of Perform ance'. Canadian-American Slavic Studies, 19, 426-442.

Hinden, Michael

1981a 'Nietzsche's Quarrel with Euripides'. Criticism, 23, 246-260.

Ivanov, Vyacheslav

1986 'Annensky as Dramatist'. The Russian Symbolist Theatre, 121-125. See Green 1986.

1986a 'The Need for a Dionysian Theatre'. The Russian Symbolist Theatre, 113-120. See Green 1986.

Kriger, M.

1950 'Otravlennaja tunika'. Grani, 8, 109-114.

Mandelshtam, O.

1979 The Complete Critical Prose and Letters (ed. Jane Gary Harris). Ann Arbor.

1986 The Noise of Time (ed. Clarence Brown). San Francisco. 'Nenapechatannoe'

1921 Dorn iskusstv. No.. 1,

Nicholson, Reynold A.

1962 A Literary History of the Arabs. Cambridge.

Nietzsche, Friedrich

1968 'The Birth of Tragedy'. Basic Writings of Nietzsche (ed. Walter Kauftnann). New York.

Odoevceva, Irina

1968 Na beregach Nevy. Washington.

Rosenthal, Bernice (ed.)

1986 Nietzsche in Russia. Princeton.

Rusinko, Elaine

1977 'K sinej zvezde: Gumilev's Love Poems'. Russian Language Journal, Vol. 31, 109, 155-166.

1979 'Gumilev in London: An Unknown Interview'. Russian Literature Triquarterly, 16, 73-85.

Sabine, George H.

1961 A History of Political Theory. New York.

Sechkarev, V.

1966 'Gumilev — dramaturg'. N. S. Gumilev. Sobranie sochinenij, Vol. 3, iii-xxxvii. See Gumilev 1968.

Segel, Harold B.

1979 Twentieth-Century Russian Drama. New York.

Struve, G. P.

1970 'Iz moego archiva. Pis'ma M. F. Larionova o N. S. Gumileve. Iz pisem B. V. Anrepa'. Mosty, 15, 401-412.